It's Time to Bring Back Lunatic Asylums

Society deserves better.

"Don't remove a fence until you know why it was put up"

G. K. Chesterton

This week in New York City, the trial of Daniel Penny has officially begun. The former Marine is being charged with manslaughter and criminal negligence in the death of Jordan Neely, a homeless and mentally ill subway performer who threatened passengers on a train and was restrained by Penny. A four-minute video by onlookers show Mr. Neely on the ground grappling with Mr. Penny. That he is being charged in the first place instead of receiving a key to the city is a miscarriage of justice, and an indictment of our current state of affairs.

Some criticize the emphasis made on Neely’s mental illness and drug addiction as the crux of the incident, with a local Brooklyn BLM organizer Imani Henry stating, “Jordan Neely was loved in his communities,” Henry said. “He was a brother; he was a community member. He was a performer — to continue to keep just focusing on his mental health condition is just unfair and wrong, because we are not simply one component of our lives. We are full and complex people.”1

While there is a sliver of truth to the statement that people are composed of more than one facet of their lives; whether it be a career, or role in a family, Mr. Neely’s mental state and lack of personal capacity to make rational decisions are the main deciding factors that led to his death. That he was on a city list known as the Top 50 for New Yorkers who are considered the most severe individuals with mental illness is a testament to the reality of his condition. Why is this subset of the population identified as posing a huge risk to society allowed to wander freely among us? This is the scene across the nation in many of our largest cities, who are beset with seemingly intractable problems handling those who cannot function in society.

And no, this isn’t a clarion call to institutionalize the entire homeless population as some sort of silver bullet solution. Homelessness does not automatically equate to someone being a risk to the general public. Yet, a clear-eyed look at the rapidly increasing number of deranged and potentially dangerous people who are allowed to roam the country as if in some open air sanitarium needs to be addressed.

Civilizations throughout recorded human history understood that there was a small subsection of the population that could never, for a multitude of reasons, remain in society without being a risk to public safety. Whether it was due to mental illness or addictions, there needed to be a place set aside away from society for them.

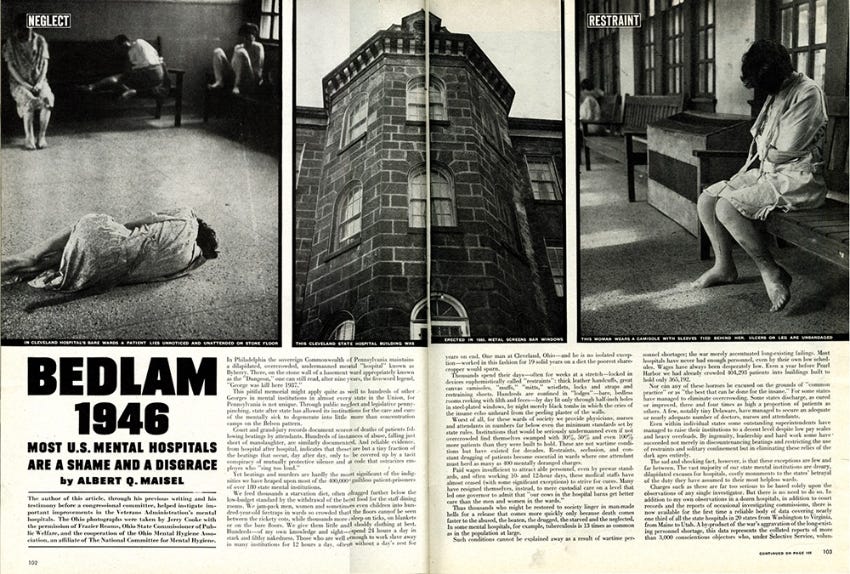

In the 20th century, mismanagement and abuses were found in a number of state mental hospitals. Patients being neglected and unsanitary conditions were recognized as a collective failure. Yet, instead of reform and improvement, the idea of housing those who present a clear and present danger to the public was abandoned almost entirely. By the 1970s, President Jimmy Carter signed the Mental Health Systems Act — which promised a more humane approach but merely transferred the burden of the mentally ill to local communities who had neither the funding or resources to accommodate this. The Reagan administration had no interest in providing grants to state communities affected by these hospital closures. (The irony of the incoming president Ronald Reagan being shot by John Hinckley, an untreated schizophrenic, is hard to miss.)

The fruits of those decisions nearly five decades ago can be seen in the news daily. There are too many examples to choose from where leaving this issue to fester has turned deadly.

The attack, which appeared to be random, and which the police said had been committed by a man with a history of mental illness who may have been homeless, immediately brought new urgency to several of the city’s most pressing concerns: a rise in some forms of violent crime, in areas including the subway; a debate about how to deal with the hundreds of homeless people who seek refuge there; and a transit system in desperate financial straits struggling mightily to lure back riders.

It also poses a steep challenge to the two-week-old mayoralty of Eric Adams, a former police captain who ran as a crime-fighter with a heart for the dispossessed. Only nine days before, the mayor had announced with Gov. Kathy Hochul a plan to achieve police “omnipresence” in the subways while also stepping up outreach to homeless people by trained mental health professionals. Saturday’s was the second violent death in the subway in two weeks.

A “random” attack the NYT reports. No one could have known or prevented this. It isn’t like he displayed a pattern of behavior to authorities.

The police said that he had had at least three previous encounters with the authorities related to mental health problems. Minutes before Ms. Go was pushed, he had confronted another female rider, who was not Asian, and put her in fear that he would push her to the tracks, they added.

Oh.

Lunatic asylums had a purpose in the past, and they need to come back. Society should not have to live amongst those with uncontrolled severe mental illness in one huge open air sanitarium nation.

You can now support my work here with Buy me a Book.

The fact that Penny is White and Neely was Black plays a huge factor in the public court of opinion, but for this essay the focus is on the need for mental institutions to house the severely (and dangerous) mentally ill.

A lot of the push was as anti-psychotics were introduced, they thought the invalids could function in society again. It's clearly not true for a significant population. The guy Penny eended up killing was arrested something like 42 times. About 90% of our homeless problems could be handled by simply stating after the first violent outburst "Either six months in jail or institution. Pick one."

Part of being clear-eyed about the problem and response is wrapping our heads around the fact that the asylum will not be a pleasant place in any way, shape or form.

It will be filled with people who will be a danger not just to themselves but to those with whom they are warehoused and the staff tasked with taking care of them.